In the last course, we looked at medical coding in the real world. Now we’ll turn our focus to medical billing. In this course, we’ll go through a few examples and show you how to create claims

Example 1

Let’s start off by looking at the first example from our previous course on everyday medical coding. If you’ll recall, after examining the patient and performing a pathology test, the doctor diagnosed the patient with streptococcal pneumoniae and prescribed a two-week regimen of antibiotics.

From that medical report we got these codes.

Procedure codes:

- 992013-4120F, new patient visit of low complexity, with the prescription or dispensation of antibiotics

- 86060, antistreptolysin O titer (Pathology)

Diagnosis code:

- 481, pneuomococcal pneumonia [streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia]

The coder would also pass us all of the relevant information for the claim in the superbill, and we’d then enter that into a medical claim. We’re going to be working with a simplified version of the CMS-1500 form for this Course.

The CMS-1500 form has 33 “elements,” or fields where the biller must enter in data about the patient, the patient’s insurance, the provider, the procedures, and the cost of the procedures, among other things.

Elements 1 through 20 are informational fields that include spaces to list the patient’s name, ID number, DOB, address, insurance policy number, and other vital information. These elements also include fields that indicate whether the patient is the subscriber (the person paying for insurance) or is merely covered by that insurance (as in the case of children on their parent’s insurance). For the most part, these fields are self-explanatory, and the information you need to fill them in will be provided by the superbill. For the sake of brevity, we’ll move right to the most important section of the claim.

Once we get to Element 21 we start getting into the meat of the claim. Billers enter the diagnosis codes into Element 21. The next relevant Element is Element 24. Element 24 is divided into six horizontal rows. In these rows, you enter the date of the procedure, the procedure code, and you re-enter in the procedures codes and re-enter the diagnosis codes from Element 21, next to their relevant procedure code. Remember, diagnosis codes on claims are used to demonstrate medical necessity. Element 24 is where we put the what (the procedure) and the why (the diagnosis) of the medical service. Element 24 also includes a column where the biller can list the charges for each procedure. We’re going to get to a visual representation of Element 24 in just a moment, but first, let’s look at the last few important Elements.

Element 25 is the field where the biller will enter the patient’s taxpayer ID. Element 26 is the patient’s account number with the provider. We’ll skip to Element 28, which includes the total charge of the procedure. Element 29 includes the amount paid by the health insurance. This is the amount the biller is asking the payer to pay, not the amount the payer has already paid.

Element 30 is the balance due for the procedure, which is arrived at by subtracting the amount paid (Element 29) from the total cost of the procedure (Element 28). The Balance is the amount that will be passed on to the patient.

Elements 31 and 32 are fields where the biller can put in information about the provider (including the service facility location and the NPI). The final Element, Element 33, is a space where you must enter the information about the provider/billing party.

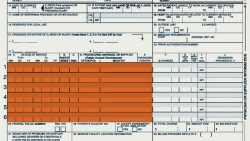

Let’s take a look at a simplified table of Element 24. We’ll use our first example to enter in the codes. (Note that we’re actually leaving off a few columns to the left of Column F. For the sake of this simplicity, we won’t be getting into the information there).

You’ll see that we attach the diagnosis codes to both of the procedures we enter. That’s because we need to justify the medical necessity for both procedures.

Before we get into more detail about this example, we’ll have to discuss charges. Private practices may set the cost of their procedures, but they should align closely to the Medicare costs of a procedure. The Medicare cost of a procedure is determined by evaluating the Relative Value Units (RVU) of the procedure. These RVUs depend on the amount of time the procedure takes (the Work RVU), the cost of that time (called the Practice RVU) and the likelihood of complications for that procedure (the Malpractice RVU). These are each multiplied by a geographic practice cost index and added up. These in turn are multiplied by a conversion factor, which is the dollar amount per RVU.

So, for the sake of this example, let’s say the cost of the E&M procedure is $200. The cost of the Pathology procedure is $300. We’d put each of those in Column F next to their respective procedure.

That brings the total cost of the procedure to a nice round $500. That’s what we’d put in Element 28. Let’s look at those Elements now.

How much the payer pays depends on the subscriber’s insurance agreement. For this first example, let’s say the our patient with pneumonia has a basic indemnity agreement, for which he owes a $200 deductible, and a $50 co-pay. After he’s paid that amount, his insurance will cover the rest of the procedure. The deductible and the co-pay have already been assigned to the patient, so the first $250 will be left off the bill. Instead, the amount paid by the pay will be listed as $250, and the balance will be zero. Let’s look at Elements 24 – 30 together.

That, in a very simplified way, is what a medical claim looks like. This gets sent to the payer and, if its approved, gets sent back to the biller for their records.

Let’s look at our second example, and throw in a few new elements.

Example 2

Our second patient is the 67-year-old female with appendicitis. If you’ll recall, this example involved a lot more codes, because it was a much more complicated set of procedures. The codes we came up with in the last example were…

Procedure:

- 99284, (Emergency department visit for a condition that requires urgent evaluation by the physician… but [does] not pose an immediate significant threat to life or physiological function)

- 76705, ultrasound, abdominal, real time with image; limited (e.g. single organ)

- 44970, laparoscopy, surgical, appendectomy

- 00840-P3, Anesthesia for intraperitoneal procedures in lower abdomen including laparoscopy; not otherwise specified; patient with severe systemic disease

Diagnosis:

- 540.9, Acute appendicitis without mention of peritonitis

Now that we’ve reviewed the codes, let’s just right into entering the information in the proper elements.

So now we’ve got the bulk of the claim filled in, but we’re missing the amount and balance due. (Bear in mind also that we’re just throwing out numbers in Column F. Those are not meant to accurately represent the cost of the procedures in this example).

In order to determine the amount and balance due, we have to know what kind of coverage our patient has. Our patient is 67 years old, which means she qualifies for Medicare. And, sure enough, she’s on traditional Medicare, which covers hospital services like the procedure above. Let’s say she has $400 left to cover her deductible. We’d take that out right away, so the amount left to cover is $1,495.

Medicare Part A can work as a co-insurance. For our example, let’s say the patient has a 80-20 coinsurance. That means Medicare owes 80 percent of the cost of the procedure, while she’ll owe the remaining 20 percent.

So we take 80 percent of the 1495 ($1,196) and put that in Element 29. That makes the balance for the procedure (i.e., what the patient owes), $299. Let’s look at the completed Elements.

And there you have our second claim, or at least the parts of it that are most relevant to the reimbursement process.

As you can see, the billing process requires a working knowledge of what codes are and how they work, in addition to proficiency in the monetary side of healthcare. You’ll need to know what codes are, how they work, but you’ll also need to know how much procedures cost, and how to tailor each claim to a specific patient’s insurance agreement.